GenAI in education is a sprawling topic, so each January I try to distill it into a single post: what’s changed, what’s most important, and what you can actually do with the technology. This is 2026’s introduction to GenAI: I’ll dig deeper into each section throughout the year.

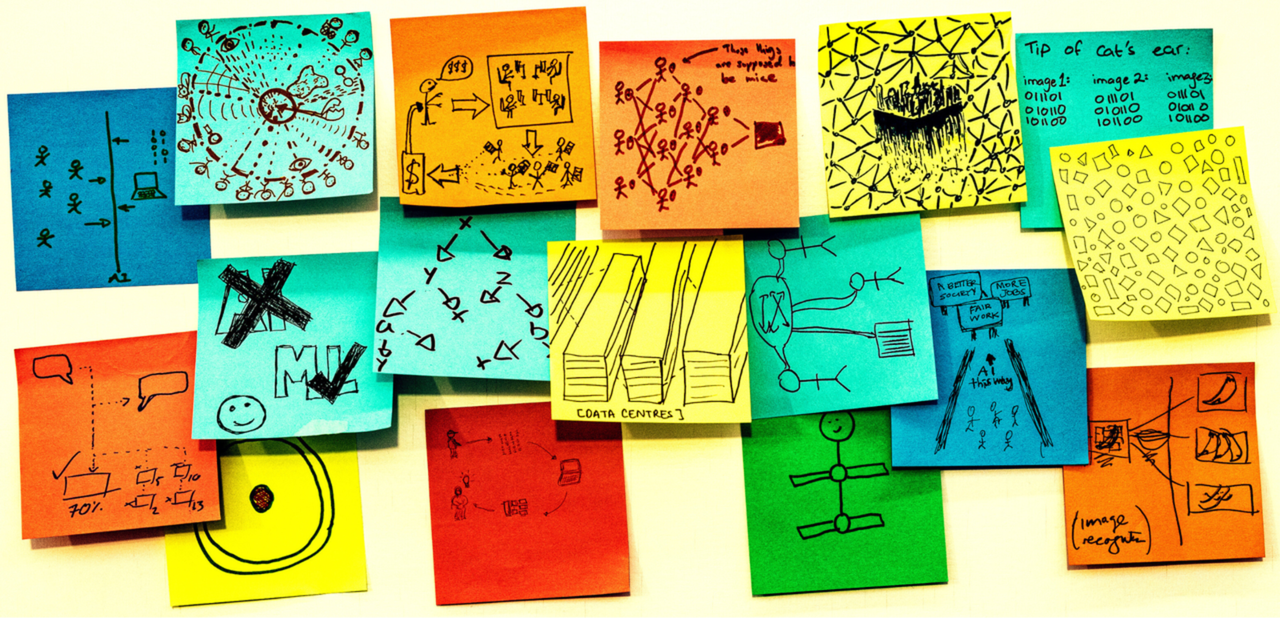

Cover image: Rick Payne and team / https://betterimagesofai.org / https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/

A new year also means a new chance to change how we engage online. I’ve written often about how social media platforms like LinkedIn deprioritise external links, meaning many of you miss the more meaningful articles on the blog. I want to make you get the full discussion of GenAI in education, not just the algorithm-friendly rage bait.

So in 2026, my work will live on my newsletter, this blog, and the YouTube channel I started last year. To make sure you don’t miss these updates, I invite you to join the newsletter community right here:

Table of Contents

- What is Generative Artificial Intelligence?

- Text, image, audio, video: What’s out there?

- Which GenAI products are educators and students actually using?

- What are educators worried about?

- What are students worried about?

- How are schools responding to GenAI in policy and in practice?

- “Cheating”, assessment, and talking to students about GenAI

- Stay in touch in 2026

- Further Reading

What is Generative Artificial Intelligence?

To kick off this discussion, we need a clear understanding of what generative artificial intelligence (GenAI) actually is. There is still a lot of misinformation and misconception around the technology, not helped by the ongoing hype and “magical thinking” of the AI developers.

In fact, as I was writing this post, I came across a share from Ray Fleming – cohost of the AI in Education podcast – which highlights the problem. In the survey Ray shared, almost a third of people interviewed believe GenAI is just “guessing” based on patterns. That’s close, but not entirely true. Even more concerning, 45% of respondents believe AI works by looking up information in a vast database. I’ll explain why that is a particularly risky perspective.

When we conceptualise GenAI like a search engine – something which uses indexing to store and retrieve information – we can easily fall into one of the biggest GenAI traps: trusting what a chatbot says.

A large language model like GPT does not use a database of information. Instead, the model is trained on a large dataset of content, and an algorithm used to create a dense network of probabilities. This is essentially a very sophisticated predictive model. If the training data is text, the model learns to output text. If the training data is images, the output is images, and so on.

It is crucial that educators wrap their head around the basics of how GenAI models work, because it allows us to speak clearly with students about what these applications can and cannot do.

Because of the way they are built GenAI models can:

- Produce novel content in styles similar to the training material

- Learn (“memorise”) and reproduce content that replicates training material

- Transpose data from one form to another, for example creating an image from a text prompt, or a text description from an input image

- Recognise and apply patterns, such as summarising text, translating between languages, or reformatting information

- Generate plausible-sounding but entirely fabricated information (hallucinations)

- Perform reasoning-like tasks by drawing on patterns in how problems and solutions were presented in training data.

Because of the way they are built GenAI models cannot:

- Know whether the output is true or false

- Access real-time or up-to-date information (unless connected to external tools like web search)

- Reliably cite sources, since they don’t retrieve from a database of documents

- Guarantee consistency (the same prompt may produce different outputs)

- Understand content in the way humans do; they operate on statistical relationships between tokens (numerical representations of the training data), not meaning.

None of this is to say that GenAI models are useless. There are many applications for the multimodal GenAI available to us in 2026, some of which I’ll outline later in this article. But we need to know about both the strengths and the limitations.

For more information about how GenAI models are built, my article on the AI Iceberg should be your next stop:

Text, image, audio, video: What’s out there?

The “sophisticated predictive text” analogy is useful for understanding how things like ChatGPT work, but it does minimise some of the capabilities of the leading models in 2026. Most of the major applications – ChatGPT, Gemini, Copilot, Claude, and so on – are now multimodal, meaning they can take text, image, audio (such as speech), and sometimes video as input, and produce many of those modes as output.

The sheer volume of multimodal GenAI applications is overwhelming. There are literally hundreds of thousands of applications which claim to offer multimodal AI, and many of them are targeted at educators. The most important thing to understand here is that the majority of them are simply websites built on top of the major AI models, and can be safely ignored.

If someone sidles into your inbox or LinkedIn DMs with an offer to “revolutionize the way you do lesson planning in your [insert subject here] course”, or “create slides and images for [your curriculum] in seconds with AI” then the chances are they’ve slapped a couple of lines of instruction on top of the basic GPT model or an open source image generator.

In my professional learning sessions and my own work, I stick to a handful of applications across all of the modes. Some are multimodal, and others just do one or two specific things, and do them well. Most of them are reasonably well-established. Here’s a (non-exhaustive) list:

Which GenAI products are educators and students actually using?

While the number of products on the market is overwhelming, in my experience educators and students are really only sticking to a handful of the major players. ChatGPT is, of course, the most prevalent. For many people, ChatGPT is AI, and OpenAI’s “first mover advantage” certainly comes into play. When the product launched in 2022, very few people had used large language model based technologies. OpenAI cornered the early market and have been increasingly aggressive in trying to hold on to that lead.

However, the reality in schools is that products from new companies like OpenAI have to compete with edtech incumbents Microsoft and Google, and many schools have followed their existing enterprise licenses and adopted Copilot or Gemini over ChatGPT. Honestly, this might not be a bad thing.

Up until 2024, I was resolute that ChatGPT outperformed the other major chatbots. That has changed over the past couple of years, and Google Gemini is now as good as or better than OpenAI’s product in many tasks. Anthropic’s Claude also beats ChatGPT in many applications, and both Google and Anthropic are (marginally) less offensive in terms of their business ethics than OpenAI, though that’s not really saying much…

Microsoft Copilot is still something of a sticking point: it is marketed into schools as “safe and private“, but it is really just another product built on top of OpenAI’s GPT model. Frustratingly, it’s not even as good as ChatGPT: anyone who has used Copilot on the web will know that the product is far behind other leading models. Essentially, forcing staff to use Copilot is unlikely to work for anyone trying to get the most out of GenAI, and it’s highly likely that they’ll instead turn to ChatGPT, Claude and Gemini and just not tell anyone.

Adobe Firefly remains a popular product in schools, and one of the only GenAI applications with a full K-12 license. Whether students should be using AI in K-6 is another conversation entirely, but the clear terms and conditions are appreciated by many teachers, especially when compared to the movable feast of other similar products like Canva (13 and over), Copilot (formerly 18, now 13), Claude (18+) and ChatGPT (?!). Google Gemini removed their age restrictions in late 2025, but again the changes have been somewhat confusing and poorly communicated, including via email blasts to parents to say “congrats, your six year old can now use Gemini. Here’s why this is your problem…”

In terms of out-of-class student use, which let’s face it is really the most important metric, I have some entirely opinionated and anecdotal data based on my conversations with students in 2025.

The highest volume is again ChatGPT. Every student I spoke to – certainly in Years 7-12 – knew about or used OpenAI’s product. This was closely followed by the “social media” chatbots: MetaAI, baked into Facebook, Instagram, and WhatsApp; Snapchat’s AI companion; and to a lesser extend companion chatbot sites like Character and Replika (more on those later).

Next in line was an acknowledgement of the “school endorsed” products like Copilot, Gemini, and platforms built by schools, sectors, and educators. These were, admittedly, mostly used when the teacher was looking. Since they’re often not as user-friendly or powerful as the alternatives, it’s hard to blame students for switching tabs as soon as possible.

Thankfully, at the bottom of the list, is X’s Grok chatbot. I say thankfully because Grok is a problematic product hosted on a problematic platform, and owned by a very problematic company. But hey, that’s just my opinion, man… The students’ opinion, which counts for much more, is that X is a boomer platform for old white men, and students don’t really know what it is. Fair enough.

What are educators worried about?

Educators are worried about a lot of things. I’ve been one for almost twenty years, and trust me, I’m always worried about something. For GenAI, these concerns are wide-ranging: cheating, academic integrity, deepfakes, critical thinking, the erosion of democracy and autonomy…

Many concerns are valid. Some are fuelled by negative media hype, and others by genuine classroom experience. Some fears are fuelled by personal biases against technologies in the classroom, and others by the care and compassion good educators have for their students.

On this blog, I’ve tried to balance the arguments for and against AI for the past four years. It’s a tightrope act, and I frequently fall off one way or the other. It’s easy to write how-to posts about shiny new toys. It’s also easy to stand up on the stirrups of the ethical high horse and yell at everyone. You can expect more fence-sitting in 2026, as I still come to terms with the implications of GenAI (and as my own children continue their journeys through school, with increasing access to digital technologies).

Here are some of the things educators are most worried about, based on my 2025 mailing list surveys, conversations with staff, and polls taken during professional development. It might come as a surprise that “academic integrity” is far from the most pressing concern when I speak with most teachers.

How to use GenAI: Teachers want concrete, classroom-ready examples of how to use GenAI well – lesson design, planning, feedback, and student use – beyond abstract principles and hype.

Assessment integrity & cheating: It’s there, but only in 14% of responses. Ongoing concerns about AI-generated work undermining authenticity, trust, and validity in assessment, and uncertainty about how far tasks need to be redesigned will continue into 2026.

Teacher capability & time: Many teachers feel under-skilled, time-poor, or lacking confidence to experiment safely with GenAI while managing existing workload and expectations. I’ve written before about how we might conduct professional development about GenAI to make it more manageable.

Student misuse & wellbeing: Worries about over-reliance on AI, reduced thinking and writing, exposure to unsafe tools, and emerging harms such as manipulation, deepfakes, or coercive “social” chatbots.

Policy, compliance & professional risk: Uncertainty about system and school policies, fear of (teachers) unintentionally breaching rules, and a desire for clear permission structures and leadership guidance.

What are students worried about?

Whether we like it or not, students are using GenAI in all kinds of ways: good and bad. And just like the educators, students have their own concerns and fears about the technology. Again, some of these fears are influenced by media hype, but many reflect deep concerns for their future careers and studies. Some also reflect broader anxieties about technologies, society, and the environment.

In my conversations with students in 2025 there were some absolutely jaw-dropping questions, often from students as young as 12 or 13 years old. Students are – like the educators I surveyed – less concerned about the perceived “cheating” concerns of GenAI and much more interested in discussing the big stuff.

Future careers: Students (Year 7-12) are most concerned about how GenAI will affect jobs, pathways, and whether the skills they are learning now will still matter in the future.

Critical & creative thinking: Many students worry that reliance on AI could weaken their ability to think independently, be creative, or develop their own ideas and voice.

Deepfakes: Students express concern about manipulated images, videos, and audio – particularly the risks of misinformation, reputation damage, and harassment.

Environment: There is awareness and unease about the environmental cost of AI, including energy use, sustainability, and broader climate impacts.

Academic integrity: Students are concerned about fairness and integrity: who is using AI appropriately, how rules are enforced, and whether honest students are disadvantaged.

How are schools responding to GenAI in policy and in practice?

Although it might not be high on the list of concerns for classroom teachers or students, a school’s response to AI at a policy level has to be a priority. Clear policies, principles and guidelines make it much easier to define what “good” looks like. It also makes it easier to have conversations with parents, board directors, and everyone else in the community that has a stake.

I work with lots of schools in an advisory capacity, and many of these positions include an audit of existing school policies and recommendations on where to go next. You’d be surprised (or maybe not, if you’ve ever sat in a compliance meeting) how many existing policies intersect with GenAI, and might need reviewing or updating. For example:

- Academic integrity policies

- Assessment guidelines at junior, middle, and senior level

- Digital user agreements and “fair use” guides for students and teachers

- Parent device agreements

- Digital consent, cybersafety, and cyberbullying policies

- Risk and compliance documents regarding data breaches, security, and privacy

- Social media, marketing, and communications guidelines

- Media and photography consent

- Specific software licenses and T&Cs

My advice is to treat GenAI as a bigger part of the overall functioning of the school. Rather than trying to write a singular “AI policy”, I recommend a looser set of guidelines which, when necessary, point to policies like the ones above. This way you’re not reinventing the wheel, and you don’t have to update an AI policy every three months when the technology changes.

Look at the policies that you already have, and then hold them up against the various local, national, and international frameworks. For example, if you’re in an Australian school, make sure that your policies account for the guiding statements in the Australian Framework for GenAI in Schools. When you’ve done that, consider the recently published Higher Education framework, UNESCO guidance, and advice such as our AI Assessment Scale. Put it all on the table, and fill in any gaps in your existing policies.

Whichever way you decide to go, make sure that the policies and guidelines are clearly communicated to staff, students, parents and the community. Often the biggest problems I encounter in schools are irate parents who feel their child has been disadvantaged by ambiguous decisions about AI (mis)use. Get ahead of these types of concerns in 2026 by clarifying your expectations.

“Cheating”, assessment, and talking to students about GenAI

Of course, this wouldn’t be an “everything you need to know” guide without some discussion of AI and cheating. Luckily – for both the educators and the students – the divisive discourse around student misuse of GenAI has died down somewhat in the past couple of years. Classroom teachers are still concerned about misuse, but both teachers and students are coming to terms with the nuances of the technology and I see far fewer dichotomising “band it and block it” conversations these days.

There are a few areas which still come up, and I’ve addressed most of them in earlier posts:

- AI Detection in Education is a Dead End

- Generative AI, plagiarism, and “cheating”

- Can the AI Assessment Scale stop students “cheating” with AI?

- Beyond Cheating: Why the ban and block narrative hides the real threats of ChatGPT in education

- What Defined AI in Education in 2025? A Year in Review

Stay in touch in 2026

Like I said at the top, I’m really focusing on this community and the blog in 2026. I’ll still be active on a few social media channels (find me on LinkedIn, Bluesky, and Mastodon) but many of my posts there will be automated and won’t be anywhere near as in-depth as these articles.

Join the newsletter for a weekly digest from the blog, a curated list of recent media and news about AI in education, and information about my professional development and online courses.

If you’ve got any questions about GenAI in education, have feedback, or just want to chat, you can always get in touch via the contact forms on this website.

Want to learn more about GenAI professional development and advisory services, or just have questions or comments? Get in touch:

Your message has been sent

Further Reading

There’s a lot of ground to cover when discussing AI in education. I called this article everything educators need to know, and hopefully I’ve ticked a lot of boxes. But I’ve also been writing about GenAI in education for the past four years so there’s plenty more for you to read if you’re interested.

For my academic publications, books, and guest podcast/media check out my publications page.

Getting started: what GenAI is

- The AI Iceberg: Understanding ChatGPT

- Practical Strategies for ChatGPT in education

- (Re)Introduction to GenAI for Schools 2025

Teaching AI Ethics: core series + updates

- Teaching AI Ethics: The Series

- Teaching AI Ethics: Bias and Discrimination

- Teaching AI Ethics: Environment

- Teaching AI Ethics: Human Labour

- Teaching AI Ethics: Privacy

- Teaching AI Ethics: Power

- Teaching AI Ethics 2025: Introduction

- Teaching AI Ethics 2025: Bias

- Teaching AI Ethics 2025: Environment

- Teaching AI Ethics 2025: Truth

- Teaching AI Ethics: Copyright 2025

- Teaching AI Ethics: Privacy 2025

- Teaching AI Ethics: Data 2025

Synthetic media, deepfakes, and “digital plastic”

- Digital plastic: Generative AI and the digital ecosystem

- Digital Plastic: Understanding AI-Generated Synthetic Media

- Real or Fake? The AI Deepfake Game

Policy and guidelines

- GenAI Policy and Guidelines

- VINE Generative Artificial Intelligence Guidelines for Schools

- We Will Not Let OpenAI Write Our Education Policy

- OpenAI Has Come for Education

- First Impressions of ChatGPT’s Study Mode

- What the National AI Plan Means for Schools

- From Schools to Universities: Unpacking Australia’s New Framework for AI in Higher Education

Assessment, integrity, and “detectors”

- The AI Assessment Scale: Version 1

- Updating the AI Assessment Scale

- AI Assessment Scale (AIAS) Translations from Around the World

- AI Detection in Education is a Dead End

- Five Principles for Rethinking Assessment with Gen AI

- About, With, Through, Without, Against: Five Ways to Learn AI

Teacher practice, PD, and workload

- Expertise Not Included: One of the Biggest Problems with AI in Education

- Talking to Teachers About AI in Schools

- Three Dimensions of Expertise for AI

- Professional Development for AI in Schools: A Three-Dimensional Approach

- Lesson planning is a verb: why does tech keep treating it as a noun?

- “Time Saved” is the Wrong Measurement for Teacher Workload and AI

- Beyond Time-Saving: How GenAI Might Actually Help Teacher Workload

- What Do Educators Want to Learn About GenAI?

- Writing Against AI: Free Session Resources

Resistance and critique

- More From the Fence: Articles For and Against AI in Education

- Resist, Refuse, or Rationalise – Just don’t Roll Over

- The Right to Resist

Tools, agents, and “hands on” posts

- Hands on with Deep Research

- Hands on with OpenAI’s Operator

- Everything I’ve Learned so far About OpenAI’s Agents

- Hands on with Canva Code

- Building an app in a weekend with Claude 3

- GPT-5 Review: Benchmarks vs Reality of the PhD in Your Pocket

Prompts vs processes

Near-future + market dynamics

- The Near Future of Generative Artificial Intelligence in Education: September 2024 Update

- The Near Future of Generative Artificial Intelligence in Education: Part Two

- The Near Future of GenAI: December 2025 Update Part 1

- GenAI is Normal Edtech

- What Happens When the AI Bubble Bursts?

Collections and hubs

Leave a Reply