For as long as the hype has been building up around GenAI, pockets of resistance have formed to the technology and its developers. The growing resistance to AI comes from many corners: businesses who were promised the world and delivered crappy chatbots; artists and writers taking up arms against the scraping and theft of their work; and educators not just sick of students “cheating” with ChatGPT, but genuinely concerned about the future of teaching and learning.

Some of these resistances manifest as community efforts, like the 2025 open letter signed by hundreds of educators around the world. Increasingly, artists, writers, and musicians are using the tools of their trade to push back against the “tools” of AI companies that seem hell bent on putting them out of work.

In this article, I look at some of the artefacts of resistance from around the world, including a few that have landed on my doorstep in the past months.

Origin Stories

Admittedly, this is also something of a nostalgic (read, indulgent) post. I’m hitting forty, and thus due for a midlife crisis. I’m thoroughly looking forward to using this as an excuse to get away with all kinds of embarrassing behaviours. In fact, I’ve already injured myself on a skateboard – all my children got wheels of one kind or another for Christmas, and I decided that a 25-year gap was long enough to justify getting back on a board. It wasn’t.

Something else which makes me nostalgic, and which is less likely to send me to the doctor’s, is zines. Specifically, the hand-printed, rough copied, underground-distributed kinds of zines that are popular in counter cultural arts, writing, and music communities.

Believe it or not, there was a long period of my life where I was “not a good fit” for education. In my experience, this is actually true of a lot of teachers; you grind your way through school, somehow end up at university, and then fall out of the other side thinking, “hmm, I wonder if there are other ways of doing that…” In senior secondary school and university, I was in a punk band called Senseless. We did pretty well, actually. A tour of Germany, support gigs for “actual bands” like TSOL, Stiff Little Fingers and the Bouncing Souls. A couple of EPs.

Because that time existed before social media, I didn’t feel compelled to take photographs every hour and therefore there is very little evidence. But just so you don’t think I’m lying, here’s a polaroid of my first bass guitar, a rusted old pin badge I found in a drawer, and the beaten up guitar I got from my uncle’s music store in my teens and which somehow made it all the way to my office here in Australia.

Anyway… I sort of stumbled my way through university, and spent far more time hanging out in bars with bands than actually attending lectures. But in my third year, something clicked, and those two worlds finally came together.

My undergraduate course was a dual honours degree in English and American Literature. In the final year, the Am. Lit. course shifted focus to the Beat Generation and counter-cultural arts of the 50s. Right away, I could see the evolution from the 1950s through to the punk scene of the late 70s, to the 00s scene that I was part of – the DIY ethos, the rejection of mainstream culture, the same impulse to pick up a pen or a microphone and just make something, regardless of whether anyone gave you permission.

I wrote my dissertation on the topic, looking at how the Beat authors shared their work in handprinted zines, publications circled in jazz clubs and underground bars, and in public performances frequently harassed by the authorities. A year or two ago, that thesis also somehow made its way to Australia: my mum found a printed copy in a box while cleaning out her loft.

The Modern Day Zine Scene

I’m older now, and much more boring. But I still remember the hand-printed gig flyers scrawled in black marker pen and photocopied onto the cheapest paper possible. I remember sitting in university libraries, appreciating the irony of reading a carefully preserved zine that had been archived for posterity – a copy of a Ginsberg poem on yellowing paper that had somehow survived the decades despite being made to be passed around, read once, and thrown away.

I think that’s why I find such appeal in the current resistance to AI. It reminds me of a sometimes-rough but often exciting and interesting moment in my own life. And really, isn’t that what art, and literature, and music is supposed to do?

I work with GenAI a lot, and I’m frequently impressed by the capabilities of large language models, but they hardly inspire the same sense of emotion-fuelled creativity as a three-chord song or a photocopied zine held together with staples and willpower.

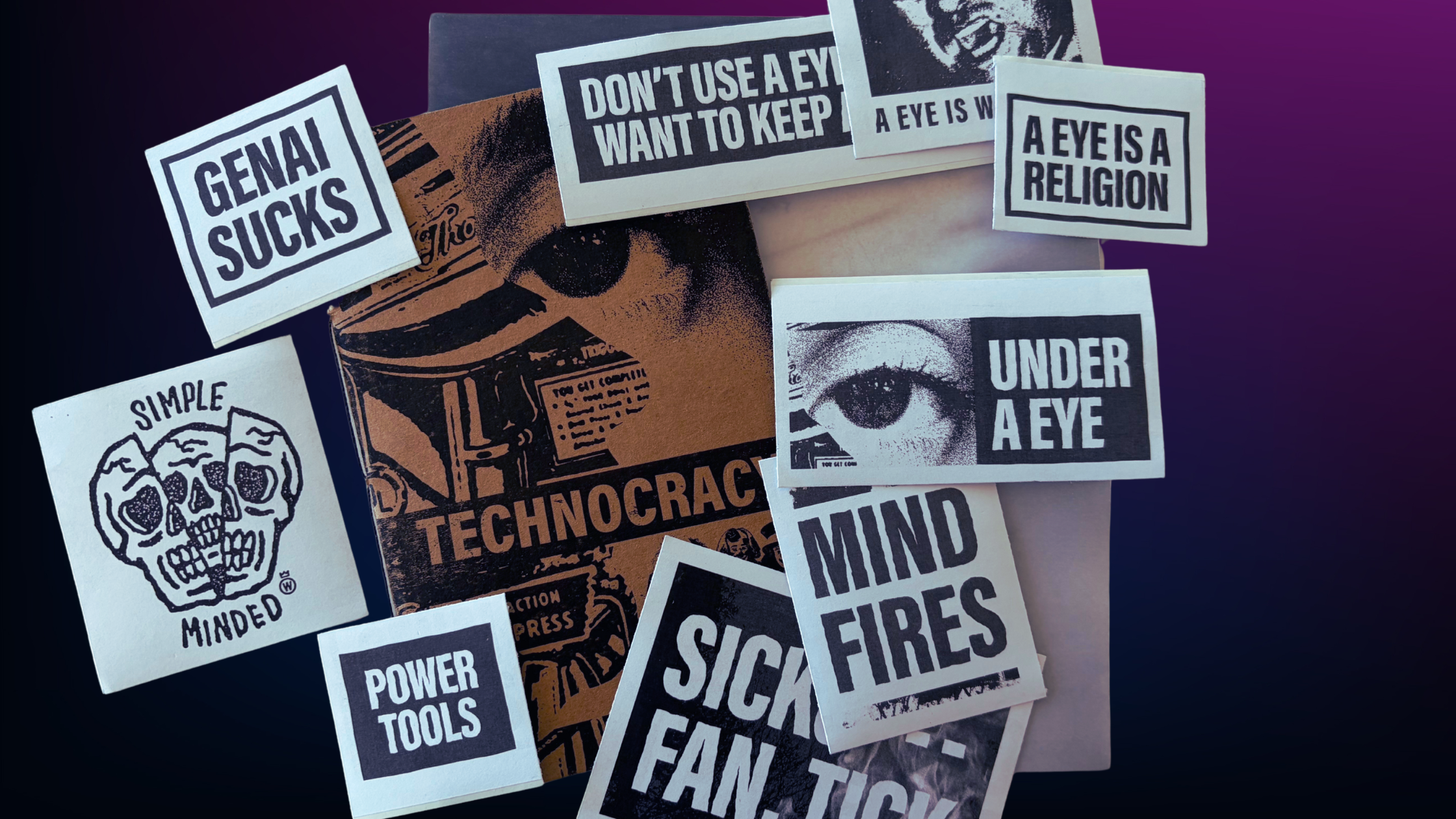

I’m obviously not alone. For the past couple of years I’ve noticed an uptick in creatives pushing back against tech in this very homegrown, DIY fashion. Late last year, I was excited to receive a copy of bart fish’s Power Tools, issue 1. It came replete with handmade stickers, stories, poems, articles, comics, even a vellum-printed, ephemeral photograph by Nick Fancher. It’s a collection that feels real. The paper is rough, the pages hand bound. It is the opposite of “artificial”.

In 2025, I took to writing weekly flash fiction, mostly about the speculative futures of AI in education. For reasons unknown, I decided that LinkedIn would be the best (maybe the most unusual) place to post these. I haven’t written one in a while, but there are people out there still posting sometimes touching, sometimes hilarious, sometimes scary stories on the platform designed for B2B sales and marketing (shout out to Shern Tee).

I put a collection of the first few stories into my own zine, albeit in a digital and much less tangible format than fish’s collection.

Luckily, I don’t need to feel too bad about not getting my stories out there in print because one of them has been included in another handmade zine – Issue 2 of Looming from Katie Conrad.

The collection has poetry, stories, prints and essays, including an essay on ethics from Australian PhD candidate Miriam Reynoldson, who was one of the instigating authors of the open letter mentioned earlier. It also arrived, importantly, with more stickers.

Mainstream Resistance

Resistance to AI isn’t limited to the DIY scene. Over the Christmas break I received a copy of Is This What We Want? A silent record of over 1000 artists protesting against the UK government’s plan to allow AI companies unfettered access to copyrighted works. The biggest names on the project include Paul McCartney (who contributed a bonus track for the vinyl release), Kate Bush, Annie Lennox, Damon Albarn, Hans Zimmer, Jacob Collier, Robert Fripp, Nigel Godrich, Pet Shop Boys and many more.

It was organised by Ed Newton-Rex, former VP of Audio at Stability AI – the company behind Stable Diffusion – who resigned over the company’s stance that training AI models on copyrighted work without permission is protected by fair use. Newton-Rex now leads Fairly Trained, a non-profit that certifies generative AI companies whose models are trained on properly licensed data rather than scraped copyrighted work.

He’s also been named one of TIME’s 100 most influential people in AI for 2025 Time, and spearheaded an open letter condemning unlicensed AI training that has gathered over 50,000 signatures.

Similar initiatives are springing up around the world, including the Human Artistry Campaign’s ‘Stealing Isn’t Innovation’ movement in the US, backed by over 700 creators including Scarlett Johansson, Cate Blanchett, Questlove, and Cyndi Lauper, which accuses Big Tech of mass harvesting copyrighted work to power generative AI platforms without permission or compensation.

In Quilicura, Chile – a community surrounded by data centres built by Amazon, Google, and Microsoft – around 50 residents recently ran a 12-hour human-powered chatbot called Quili.AI. Send it a prompt and a real person would respond: ask for an image and someone would draw it by hand; ask a question and a human would answer it. The project fielded over 25,000 requests from around the world, and was designed to highlight the hidden water footprint of casual AI prompting in a region already under water stress. As organiser Lorena Antiman put it, the campaign isn’t about rejecting the valuable uses of AI – it’s about making people think twice about the environmental cost of every throwaway prompt.

Make Something

What strikes me about all of this is how familiar it feels. The methods haven’t really changed since the Beats were passing poems around Greenwich Village bars, or since I was flyering for gigs in sticky-floored venues in the early 2000s (I’m looking at you, The Sugarmill). When people feel that something important is being taken from them, they don’t wait for permission to respond. They pick up a pen, or a guitar, or a stack of cheap paper, and they make something.

That impulse – to create something real, something imperfect, something human – is exactly what AI can’t replicate. And it’s exactly what makes the resistance worth paying attention to.

Want to learn more about GenAI professional development and advisory services, or just have questions or comments? Get in touch:

Leave a Reply