This is an updated post in the series exploring AI ethics, building on the original 2023 discussion of data and “datafication”. This post explores why and how GenAI relies on so much data collection, how AI companies are gathering the information, and what it means for education.

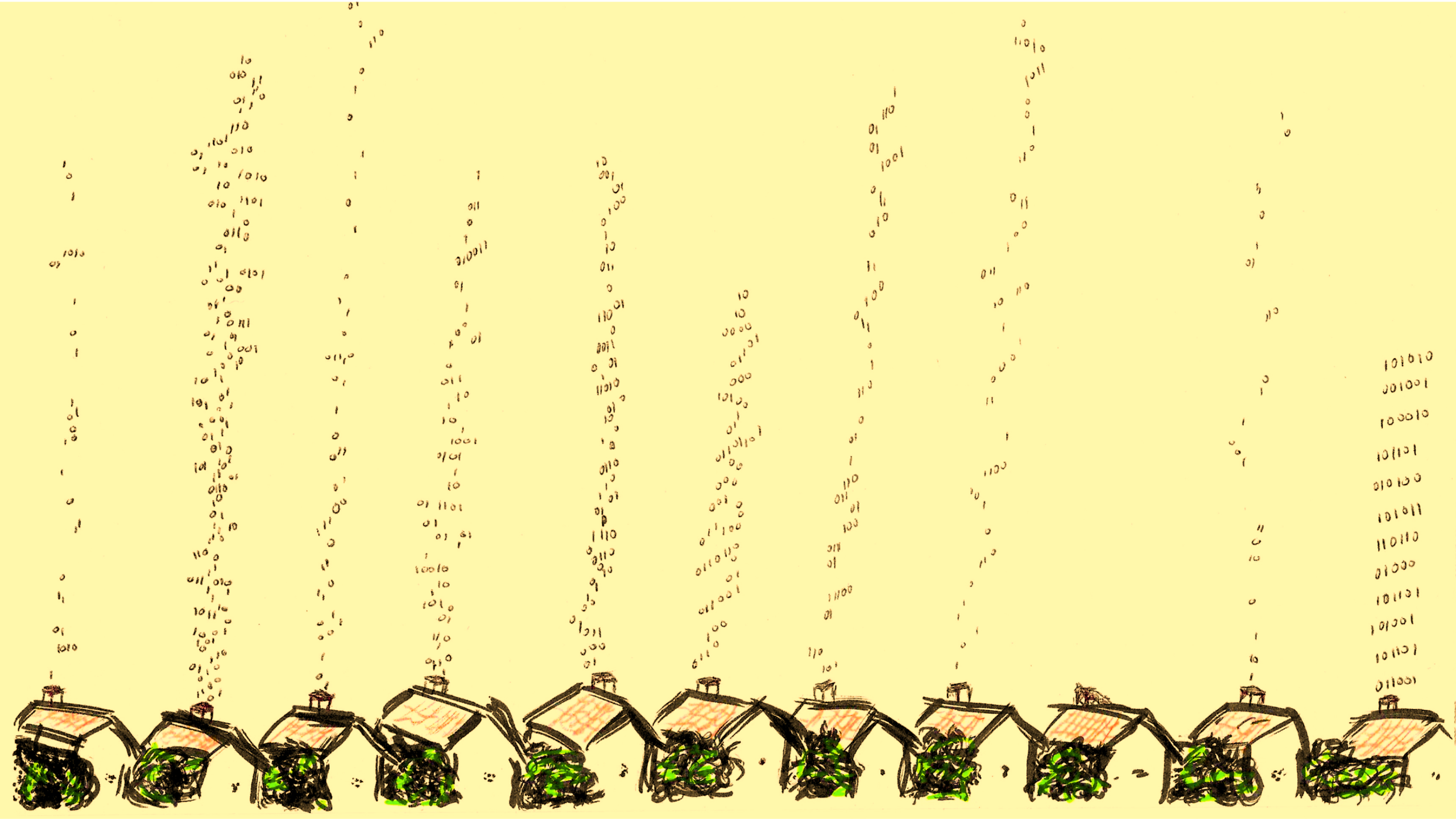

Cover image source: Joahna Kuiper / https://betterimagesofai.org / https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/

Data has become the de-facto currency of the digital age. Every interaction with technology, from the questions we ask AI chatbots to the time we spend watching educational videos, generates data that companies collect, analyse, and monetise. The scale of this data collection has exploded with the rise of GenAI. In 2025, ChatGPT alone reportedly processes over 1 billion prompts per day, creating an unprecedented stream of data about how people interact, study, and work with chatbots.

The increased collection of data from chatbots also represents a shift in how human experiences are quantified and turned into commercial products. When students and schools use AI tutors and other so-called “personalised” learning systems, each interaction feeds into vast data ecosystems that shape everything from commercial targeted advertising to algorithmic decision-making about students’ futures.

British data scientist Clive Humby famously stated “Data is the new oil” – a phrase which has become a cliché in discussions of digital technologies. But unlike oil, data extraction often happens invisibly, without meaningful consent, and with consequences that extend far beyond the moment of collection. This article explores the ethical implications of turning every aspect of students’ lives into data, examining how GenAI systems harvest information, where that data goes, and what it means for education.

Check out the original series of article for more teaching ideas:

Understanding the scale of data collection

The explosion of GenAI has enabled data collection on a scale previously unimaginable, even when compared to the notoriously data-intensive practices of social media and search. ChatGPT reached 100 million users in just two months after its November 2022 launch: the fastest-growing consumer application in history at the time. By February 2025, it had grown to 400 million weekly users, and by August 2025, that number had reached 800 million.

Every one of these interactions generates data. According to OpenAI’s own research on how people use ChatGPT, the company analysed 1.1 million sampled conversations from their user base, examining everything from conversation topics to user demographics to work-related versus personal use. The study suggests around a third of consumer use is work-related, with the three most common conversation topics being “Practical Guidance” (29%), “Seeking Information,” and “Writing” (collectively accounting for 77% of all conversations).

But what happens to all this data?

By default, ChatGPT stores every query, instruction, and conversation indefinitely unless users manually delete them. According to OpenAI’s privacy policies (plural, because they actually have different policies for Europe than the rest of the world), OpenAI collects both user-provided data (prompts, questions, responses, uploaded files) and system-generated data (timestamps, usage statistics, device information, IP addresses, approximate location, payment details). All conversations are stored on OpenAI’s servers in the USA, and according to the company’s privacy policy, this data may be used to train and refine AI models through a process called “fine-tuning,” which can involve human reviewers examining conversations.

While users can opt out of having their data used for model training, a 2024 EU audit found that only 22% of users were aware of these opt-out settings. The default setting means most interactions contribute to an ever-growing dataset that shapes future AI behaviour. Even users who enable “Temporary Chat” mode should note that while these chats are deleted after 30 days, they may still be used for training if the opt-out is inactive.

Jamillah Knowles / https://betterimagesofai.org / https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/

Case Study: AI Conversations Become Advertising Gold

In late November 2025, a leak from ChatGPT’s Android app beta suggested something many users suspected but few wanted confirmed: OpenAI is preparing to introduce advertisements into ChatGPT.

X user Tibor Blaho reportedly discovered explicit references to an “ads feature” with “bazaar content,” “search ad,” and “search ads carousel” buried in version 1.2025.329 of the Android app code. While no official announcement has been made, the infrastructure appears to be being built for a new revenue stream that could definitely change the relationship between users and the chatbot.

As Bleeping Computer writer Mayank Parmar commented, “what most people don’t understand is that GPT likely knows more about users than Google.” Through extended conversations, OpenAI stores data about users’ jobs, interests, problems, aspirations, relationships, health concerns, and personal circumstances. ChatGPT has access to the problems you’re struggling with at 3am, what career advice you’re seeking, what you’re planning to buy, and what questions you’re too embarrassed to ask another human.

This creates opportunities for what industry watchers call “hyper-personalized advertising“—ads tailored not just to your demographics or browsing history, but to your deepest thoughts and current emotional state. OpenAI CEO Sam Altman has publicly acknowledged that ads are “something we may try at some point,” while noting the risks: “If ChatGPT were accepting payment to put a worse hotel above a better hotel, that is probably catastrophic for your relationship with ChatGPT.”

But that seedy little cat may already be out of the bag. With ChatGPT generating $3.7 billion in revenue in 2024 but still facing questions about long-term profitability, and with the platform’s computational costs estimated at $700,000 per day, advertising represents a tempting new revenue stream. The leaked code suggests ads will initially be limited to search results – similar to Google’s model – but there’s no guarantee they won’t expand into other areas of the platform.

For students and educators, this raises critical questions about trust and manipulation. There’s no coincidence that the language of “hyper personalisation” has already insinuated itself into discussions of edtech. And, if an AI tutor can be monetised through advertising, how do we know its educational recommendations aren’t influenced by commercial interests? When a student asks for university entrance advice, will the chatbot recommend institutions that have paid for placement? When they seek career guidance, will they receive genuinely helpful information or carefully disguised sponsored content?

Data-Driven Classrooms: From Learning to Surveillance

Of course, the incessant pursuit of data doesn’t stop at consumer AI tools. Educational institutions have accepted data collection on an unprecedented scale, often in the name of “personalisation” and “improved outcomes.”

Learning Management Systems (LMS) like Canvas, Blackboard, and Google Classroom have become the backbone of modern education, and with them comes constant data extraction. These systems track everything from student logins and page views to time spent on tasks, click patterns, quiz performance, discussion board participation, and assignment submissions. More sophisticated systems claim to analyse behavioural data, creating detailed profiles of student engagement patterns and apparently predicting future performance.

The learning analytics market was valued at $4.2 billion in 2024 and is projected to reach $18.6 billion by 2034, growing at 16.1% annually. This growth is driven by what industry reports describe as “the accelerating digitization of educational institutions, increasing demand for personalized learning experiences, and the growing emphasis on data-driven decision making.”

But what does “data-driven decision making” mean for students?

According to a study published in the Journal of Computers in Education, LMS platforms analyse students’ “persistence and consistency of engagement behavior” to predict academic performance and identify “at-risk” students. The study notes that “educators can personalize instruction based on individual students’ engagement patterns, preferences, and needs” and can “generate predictive models that provide early warnings on students’ performance.”

While this sounds beneficial, it raises serious questions about algorithmic bias, self-fulfilling prophecies, and student agency. For example, machine learning models are less accurate at predicting success for racial and cultural-linguistic minorities, meaning these systems may systematically disadvantage certain groups. When an algorithm flags a student as “at-risk” based on their engagement patterns, does that help or harm? Does the intervention support the student, or does the label itself create a stigma that affects how teachers interact with them?

Jamillah Knowles / https://betterimagesofai.org / https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/

Moats, Lakes, and Oceans: Where Does All the Data Go?

To understand why companies collect so much educational and user data, we need to follow the data and examine the economic incentives at play. Companies gather vast amounts of information for various reasons, and AI plays a significant role in many of these processes:

Targeted Advertising and Commercial Profiling: As we’ve seen with the ChatGPT ads leak, one primary driver is targeted advertising. AI algorithms analyse collected data to predict the most effective ads for each user, to maximise return on investment for advertisers.

For students using AI tools, this means their educational struggles, career aspirations, and financial concerns may all become fodder for commercial targeting. A student researching college options might find themselves targeted with ads for expensive test prep services. A student asking about mental health might see ads for therapy apps or wellness products. A student anxious about using AI will receive targeted ads for “Humanisers” and other tools designed to evade detection. The line between helpful recommendation and commercial manipulation becomes increasingly thin.

Training Data for AI Models: OpenAI has been explicit that consumer conversations (for free and paid users who haven’t opted out) may be used to train future models. While ChatGPT Enterprise, Team, and Edu customers have data protection guarantees, the vast majority of users – including most students – do not. Their conversations become part of the training data that shapes how AI systems respond to everyone.

This creates a feedback loop: students’ interactions improve the AI, which makes it more student-friendly, which attracts more students, which generates more data. Companies like OpenAI frame this as continuous improvement, but it also represents an unprecedented extraction of intellectual labor. Every time a student uses ChatGPT to work through a problem, they’re also training the AI that the company will then sell to others.

Predictive Analytics and Behavioural Profiling: Educational data platforms use collected information to create detailed student profiles for various purposes, including risk assessment, performance prediction, and intervention targeting.

These profiles can follow students throughout their educational careers and potentially beyond. Grades, behavioral data, engagement patterns, and even biometric information (from AI proctoring systems that track facial expressions and eye movements) become part of a comprehensive data shadow that may affect future opportunities.

Third-Party Data Sharing and Ecosystem Building Perhaps most concerning is that collected data often doesn’t stay with the original platform. Companies may share user data with third parties such as data brokers, advertisers, or business partners. In the education sector, many AI tools used by teachers are not specifically designed for educational use and may not be protected under school data policies. When teachers use consumer-facing versions of ChatGPT or other AI tools with student data, that information may be subject to different privacy standards than school-approved platforms.

The Future of Privacy Forum notes that in the US there are over 128 state student privacy laws that schools might need to monitor, but enforcement is inconsistent and the technology is evolving faster than regulation.

Teaching AI Ethics: Data

Each of the suggestions below offers a starting point for incorporating data ethics into your curriculum. Every suggestion comes with a resource or further reading, which may be an article, blog post, video, or academic article.

History: How does the collection and use of big data impact the way we study and interpret historical events? How might data-driven historical research create new biases or misrepresentations of the past? Consider: If AI models are trained primarily on digitised texts from wealthy nations, how might that skew our understanding of global history?

English: How does data-driven analysis influence the way literature is interpreted? What happens to the “human” elements of reading when texts are reduced to data points? When AI writing tools are trained on vast corpuses of text, what voices are included and excluded?

Mathematics: How has the datafication of society transformed careers in mathematics and statistics? What ethical considerations should guide data collection and analysis? How can we ensure that predictive algorithms used in education don’t reinforce existing inequalities?

Computer Science / Digital Technologies: How do learning management systems collect and use student data? What are the implications of behavioural tracking and predictive analytics in education? How can we build systems that respect student privacy and agency?

Business Studies / Economics: How has data become a commodity in the modern economy? What is the true “cost” of “free” services like ChatGPT? How do data-driven business models affect competition and innovation in the educational technology sector? Use industry reports on edtech market values to inform your estimates.

Environmental Science: How does datafication impact the study of environmental systems? What are the trade-offs between the benefits of large-scale environmental monitoring and the energy costs of data centres that process this information?

Visual Arts: How does data collection influence the creation, interpretation, and distribution of visual art? When AI image generators are trained on millions of artworks (often without artists’ consent), what happens to creative ownership and artistic labour?

Geography / Social Sciences: How does datafication impact the study of geographical patterns and human systems? How might location data from students’ devices be used for research—and what are the ethical boundaries?

Philosophy / Ethics: What does it mean to be a person in a datafied world? If your data creates a profile that predicts your behaviour, are you still free? How should we think about consent when most people don’t understand what they’re consenting to?

Legal Studies What are the current legal protections for student data? How have laws like FERPA, COPPA, GDPR, and state-level privacy regulations evolved (or failed to evolve) in response to AI? What would effective AI data regulation look like?

Want to learn more about GenAI professional development and advisory services, or just have questions or comments? Get in touch:

Leave a Reply