For a while now, I’ve been grappling with this problem: in order to get the most out of generative artificial intelligence, you need both a level of expertise with the technology and in the domain in which you’re trying to use AI.

This is because, though powerful, large language models aren’t actually particularly good for learning and developing new skills. Rates of hallucination continue to be a problem and even with recent advances, internet connection and improvements to file upload, it is impossible to guarantee a GenAI application like ChatGPT is telling you the truth.

This makes the technology particularly problematic in education, where you would hope we’re in the business of truth, whether we’re talking about students or ourselves. It’s hard to learn something with confidence when you can’t trust the output of the thing giving you advice.

And yet, paired with domain expertise, artificial intelligence can be useful. The ability to intuitively spot errors and hallucinations means you can quickly course correct mid-dialogue with the chatbots, as long as you don’t let your attention wander.

I wrote about this in a post last year where I described this expertise problem. Earlier this year Punya Mishra also published an article mirroring those concerns. Mishra suggested a matrix of domain and technological expertise, with people falling into four quadrants.

I always love a matrix. And although they can oversimplify complex problems, I think this approach of understanding some of the risks and the potential of working with generative AI is solid.

I was thinking again about this problem recently, in light of my PhD studies and my own day to day experience with AI, when I saw a post on LinkedIn which introduced a missing piece into the puzzle. The post, shared by Jonathan Boymal, referred to a Dreyfus and Dreyfus model of expertise, and also drew on some of Lave and Wenger’s ideas of situated practice.

My PhD study draws on a community of practice model and on ideas of the situatedness of language and identity Pulling together the threads from Dreyfus and Dreyfus, Lave and Wenger, and literacy scholars like James Paul Gee, I’ve arrived at a third dimension of expertise, which is necessary to get the most out of artificial intelligence: situated expertise.

Situated Expertise

If domain expertise is academic and practical knowledge about a subject, topic or job, and technological expertise refers to the understanding of technologies like artificial intelligence, then situated expertise might be seen as something which supports and wraps around these other two dimensions. It is contextual, relational and something which develops over time.

Expertise is not just the application of knowledge, but an embodied, context-sensitive responsiveness honed through extended, emotionally engaged practice. True experts perceive and act holistically: rather than following abstract “if-this-then-that” patterns, they intuit patterns in real time, recognising which features of a situation matter. Their fluency emerges from immersed experience, so that knowing when and how to break or bend rules becomes as natural as following them. And when routine intuition falters, experts deploy a reflective capacity: stepping back to question their framing, to consider alternatives, and to engage in a self-aware dialogue with the problem at hand. In this view, expertise is a continuous, adaptive learning process, not a static accumulation of facts.

Situated expertise is the kind of expertise which develops as the person gains not only an academic understanding of their discipline, but the reflexive and intuitive response to applying that knowledge. It also determines how they apply their expertise in different contexts with different groups. For example, a skilled academic educator may be able to adjust their delivery of content knowledge to different audiences, demonstrating their situated expertise to a crowd of undergraduate students or peers in their academic field, and perhaps even the everyday person on the street.

Situated expertise isn’t something that you can just pick up. Unlike technological expertise and domain expertise, you can’t complete a couple of courses or read a few books and start to acquire the knowledge. Situated expertise is deeply human and connected, understanding that both the gaining and the sharing of knowledge is relational.

Situated Expertise and Artificial Intelligence

So what does situated expertise add to my earlier post, or to Mishra’s framing?

In my earlier article on expertise, I argued that a person needs a certain amount of both technical and domain knowledge to make AI do anything useful, but with situated expertise, we can also bring in more contextual awareness.

A person can be highly skilled in their discipline and highly skilled in using artificial intelligence, but if they are unable to contextualise and share that knowledge, then it can be a very selfish kind of understanding. It might also lead to skilled academics who fail to take into account the context of their students, their technical understanding, their moral and ethical stance on artificial intelligence.

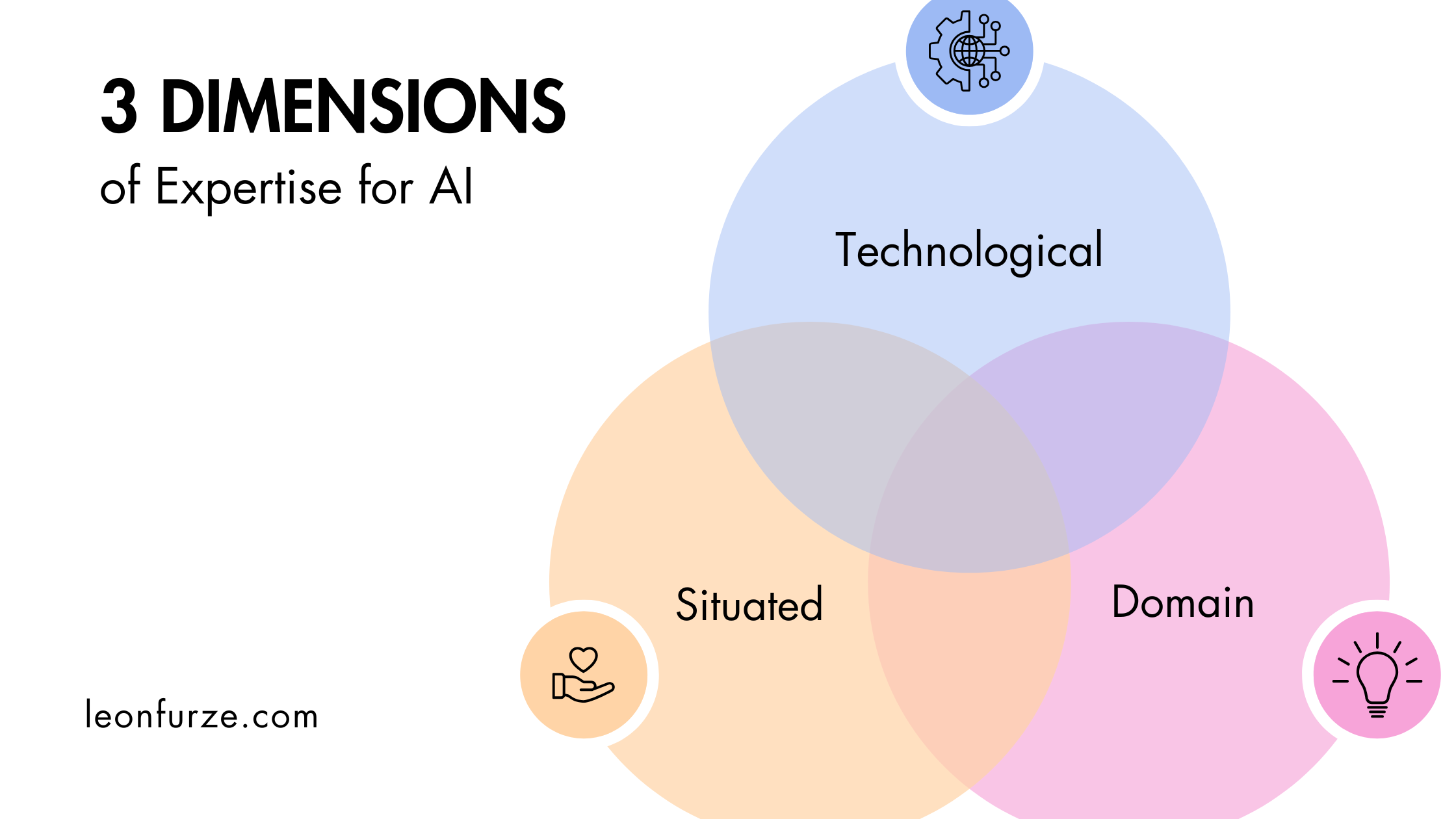

Like Mishra’s four quadrants, I’m interested in the ways these three dimensions intersect, and I’ve been playing around with a few variations on ways to express that. The most obvious is the overlapping Venn diagram.

In the overlaps, we can start to see different profiles emerging.

Technological/Domain

As described above, this is the person who is an expert in their field and an expert with technology, but who might struggle or even resist contextualising that expertise in different communities.

This might result in some of those accusations commonly levelled at academics in “ivory towers”, or of using positions of privilege to share perspectives without carefully considering context.

Domain/Situated

A person in this profile might have the advantage of both experience in their field and the ability to share and contextualise that practice. These are often great educators, passionate, engaging and knowledgeable. Without sufficient understanding of the technology, they may fall into the trap of being offhandedly critical based on conjecture, or naive to some of the issues of the technology. They might also avoid the technology entirely; not because of a conscious, engaged refusal, but simply the idea that it doesn’t apply to them and their area of expertise.

Situated/Technological

This profile includes people who know how to share, know how to build communities, and perhaps have broad or deep domain knowledge in other areas. They have a solid understanding of technology and an ability to be reflexive as the technology develops, but without domain expertise, they may stray into unfamiliar territory with too much confidence. They might speak on behalf of others, or come across as disrespectful to experts in other fields.

You see many of these types on social media: people who have quickly adapted to the technology and who know how to work a platform, but whose understanding of any particular discipline is relatively shallow.

Situated/Domain/Technological

Sitting at the center of the Venn diagram, where all three overlap, is an example of a person who’s invested significant time and energy into developing disciplinary understanding and an awareness of the technology, but also has the contextual and relational skills needed to share that knowledge thoughtfully and meaningfully in different contexts.

This is obviously an ideal, and would require somebody with established disciplinary knowledge to consciously apply themselves to learning about the technology, or perhaps somebody with existing technological skills to hone in on a particular discipline and specialise.

Three Dimensions of Expertise

One belief from my earlier writing still stands: generative AI is far better suited to those who already possess substantive knowledge than it is to novices. Every profile I’ve sketched here maps neatly onto educators or other professionals rather than learners.

Students who are beginners in all three dimensions – domain, technological and situated – shouldn’t be expected to “bootstrap” themselves to expertise with AI alone. Even a technically adept student cannot simply “prompt-engineer” their way into deep disciplinary mastery, because expertise grows from sustained practice, feedback and social context.

For that reason, this framework is most useful when applied to people who already hold at least one strong footing: a solid grounding in a discipline, a mature grasp of the technology, or the relational, contextual skills that constitute situated expertise. From there, they can work intentionally to develop the other dimensions.

Adding situated expertise to the existing axes of domain and technological knowledge reminds us that expertise is never just cognitive or procedural; it is social, relational and context-bound. Whether you are an academic, a teacher, or a practitioner in another field, the value you create with and without AI will hinge on how well you weave those three strands together.

I’d love to hear your thoughts on these three dimensions.

Subscribe to the mailing list for updates, resources, and offers

As internet search gets consumed by AI, it’s more important than ever for audiences to directly subscribe to authors. Mailing list subscribers get a weekly digest of the articles and resources on this blog, plus early access and discounts to online courses and materials. Unsubscribe any time.

Want to learn more about GenAI professional development and advisory services, or just have questions or comments? Get in touch:

Leave a Reply